Thursday July 8, 2021 | VICTORIA, BC

A perspective during the COVID pandemic

by Jalen Codrington | Island Social Trends

I recently had to make the trip from Vancouver Island over to Vancouver General Hospital for a doctor’s appointment. It was somewhat strange, to say the least.

As I’m walking to the building, I see the nurses outside on break are all sitting (2 metres apart), slouched, silently, smoking cigarettes. Even the most chipper of them has an air of weariness. They look like they’ve been through the war.

Inside, it’s business as usual. There’s a large hand sanitizer dispenser by the doors. Nobody who walks in is really using it. To access the elevator, you need to swap the mask you brought at home with one provided by the staff sitting at a desk (after they offer you a second squirt of sanitizer). The few seconds where I’m transitioning masks and my airways are exposed seems like a major faux pas inside a hospital.

Nearby, staff are cramming into the elevator. They adhere to the six-person maximum rule, but no one’s going out of their way to space themselves like you would have seen at this time last year. They’ve been dancing to this tune for 15 months now.

When I finally meet with the doctor I came to see, it’s a strange interaction. All questions I ask him, it seems at first like he doesn’t hear me. Then he replies with brief, indifferent answers, as if he couldn’t care less.

I didn’t know what to make of this. It didn’t feel like I was in a hospital during a pandemic. I was there in the early afternoon on a gloomy Tuesday, but it felt like 3:30 on a sunny Friday, and everyone just wanted to go home.

Let me be clear – none of this is to disparage healthcare workers for having lax attitudes, or criticize hospital policies. This is only to record a noticeable phenomenon.

A troubling survey:

Recently, the University of British Columbia conducted a survey among physicians working at Vancouver General and St. Paul’s between August and October 2020. The results were shocking – almost 70 per cent of physicians reported they were feeling “burnout,” and over 20 per cent were considering quitting their profession, or had already quit a position. And it’s unlikely this trend is unique to only those two mainland hospitals.

In 2019, the World Health Organization added burnout to its International Classification of Diseases, describing it as “a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed” though stopped short of classifying it as a medical condition.

Burnout is characterized by complete emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, affecting the level of care the practioner puts into their work, and their sense of personal accomplishment. In pre-pandemic times, physicians already had one of the highest suicide rates of any profession, up there with dentists and cops.

Dr. Nadia Khan, general internal medicine professor at UBC, stated that physicians who are burned out are more likely to make medical errors, which can cost healthcare organizations millions.

Heavy burden:

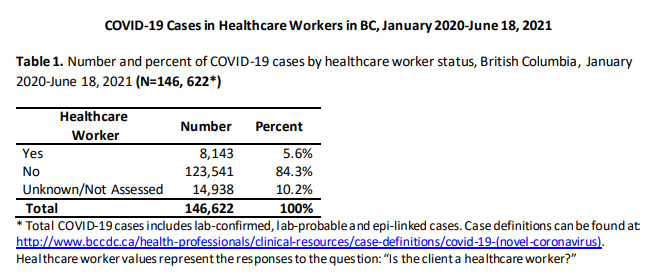

It would be a gross understatement to say workers have borne a heavy burden over this 18-month pandemic. Earlier this year, it was reported that almost six per cent of new COVID cases were among healthcare workers. The many among us who have been working from home during this pandemic have been spared the brunt of the virus.

On March 16, 2020 non-urgent scheduled surgeries were postponed to ensure hospitals had the capacity for COVID-19 patients. This resulted in 32,400 fewer scheduled surgeries. A few months later, when surgeries were scheduled to resume, health authorities had 15,373 surgeries to catch up on. As a result, operating rooms ran 5,246 hours over the previous November to February time-frame.

Gatherings are not quite so limited anymore (now in Step 3 of the BC Restart), though it’s likely many healthcare workers are still social-distancing from their friends and family. Gyms and rec facilities, where people could formerly blow off stress, haven’t been particularly accessible lately either. But instead of just focusing on coping skills, the majority of survey respondents said improving work conditions and better management of work quantity are needed to combat burnout.

As COVID-19 cases steadily decrease in BC, it’s tempting to think healthcare professionals’ exhaustion will naturally subside. Maybe it will, to some degree. But the mental effects of the pandemic are likely going to stay with us all for some time, more intensely among those in the healthcare sector. And it’s not as though pre-pandemic burnout rates are an especially attractive destination to rebound to.

===== About the writer:

Jalen Codrington is a 4th-year University of Victoria student who is working with Island Social Trends this summer as Copy Desk Editor.