Thursday January 14, 2021 | Vancouver Island, BC

by Kiley Verbowski | Island Social Trends

Approximately 25,000 Indigenous people living in remote and isolated communities within British Columbia are slated to receive the vaccine before March, which is hopeful news riding on the tail of another First Nations community outbreak on Vancouver Island.

Cases within Cowichan Tribes were confirmed on January 1, 2021 and a shelter in place order was issued for all community members on January 6 effective to the 22nd. Positive case counts are now at 73.

Cowichan Tribes general manager, Derek Thompson said that 600 doses are scheduled to be administered to community elders beginning on Wednesday January 13.

Cowichan Tribes is the largest single band in B.C. with almost 5,000 members.

Discrimination and COVID-19 outbreaks among First Nations in B.C.:

Thompson said last week that some members within his community are experiencing discrimination since Cowichan Tribes made their positive cases public.

BC Green party leader Sonia Furstenau (Cowichan Valley MLA) and North Cowichan Mayor Al Siebring have publicly denounced the racist remarks that have appeared online and uttered directly to members of the community.

Indigenous people are twice as likely to feel that people in their neighbourhood are being harassed or attacked because of their race, ethnicity, or skin colour according to data collected by Statistics Canada during the pandemic.

As of January 11, 2021 there have been 954 positive cases of COVID-19 on First Nations reserves, and 11,229 across Canada. Almost all cases have occurred since October 2020. The total number of deaths is 103.

Remote and isolated communities receiving the vaccine first:

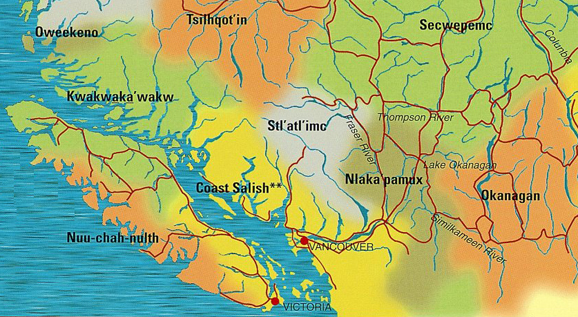

There are six Nuu-chah-nulth nations (east side of Vancouver Island) that are among the first in B.C. to be vaccinated. The communities include Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’/Che:k:tles7et’h’ First Nations, Huu-ay-aht First Nations, Ehattesaht First Nation, Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation, Nuuchatlaht First Nation and Ahousaht First Nation.

The two Kwakwaka’wakw nations (north Vancouver Island area) that are also on the priority list are the Klahoose First Nation and the Namgis First Nation.

Remote and isolated communities have been prioritized because of their limited access to health care and long distance to the nearest hospital.

The Ehattesaht nation experienced a COVID-19 outbreak in November 2020. The community of 100 people and 20 households reported 28 positive cases.

Long-lasting economic impact on Indigenous people:

A quarter of Indigenous people living in urban areas live below the poverty line, and the number is much higher for Indigenous single-parent families at 38 per cent. Many households face food insecurity and live paycheque to paycheque, which made them extremely vulnerable to the negative socioeconomic consequences of government orders aimed at curbing the transmission of COVID-19.

Fulfilling essential needs like rent or mortgage payments, utility bills, and groceries during the pandemic has generally been more difficult for Indigenous people, and 65 per cent reported a strong or moderate financial impact. Although there was little difference between the number of Indigenous and non-Indigenous workers that initially experienced job loss or reduced hours, Indigenous participants reported an overall larger financial impact. However, more recent data shows that employment among Indigenous people has been slower to recover.

Plus, according to previous evidence collected after the 2008/2009 recession, the labour market impacts for Indigenous populations will most likely be much longer lasting, and recovery even slower than for non-Indigenous people. Pre-existing vulnerabilities like wide-spread poverty and food insecurity will contribute to continued economic distress.

According to data collected in early June 2020, Indigenous participants also reported much less trust in their government and health authority’s reopening decisions. Across all levels of municipal, provincial or territorial, and federal government, trust is lower than amongst non-Indigenous Canadians.

Mental health impacts among Indigenous people:

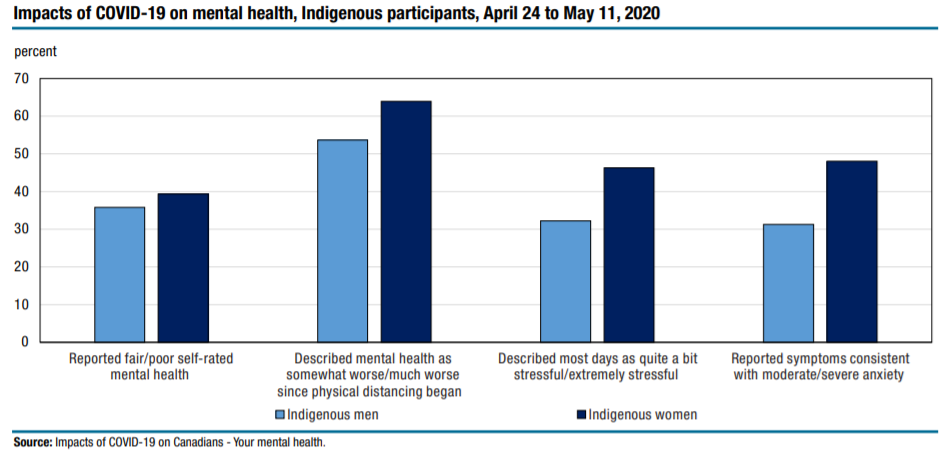

During the pandemic and ensuing socio-economic impacts, Canadians experienced a sharp decline in the state of their mental health, and reports show that the decline has been even more wide-spread amongst Indigenous populations.

According to a May 2020 survey conducted by Statistics Canada, 60 per cent of Indigenous respondents reported that their mental health has taken a nose dive, compared to 52 per cent of non-Indigenous respondents. The mental health disparities between these populations has been well-documented, and can be explained in part by the historical and ongoing abuses of colonialism including residential schools, the forced relocation of communities, and the ongoing gaps in mental health services.

Indigenous women are reporting more stress than men, and are also more statistically more vulnerable to economic instability, and risks of gender-based violence.

The increased risks of domestic violence because of stay-at-home orders has been documented during the pandemic. More than double the number of Indigenous respondents said that they are concerned about the impact of the pandemic on violence in their home than non-Indigenous respondents.

Indigenous people were also more likely to report a lower sense of safety in their neighbourhoods during the pandemic. This may not necessarily relate to higher crime rates, but the perception of safety is very important to an individual’s and a community’s well-being.

Note on the methodology of StatCan surveys:

All of the referenced data was collected by Statistics Canada using crowdsourcing surveys with varying numbers of participants ages 15 and up.

Data cannot be evenly applied to all provinces and territories, and responses do not equally represent diverse subpopulations of Indigenous peoples. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people represent three distinct Indigenous cultures within Canada, but each contain a multitude of communities with distinct cultures, languages, and traditions, and can include people living on reserves and in urban centers.

===== About the writer: Kiley Verbowski, BA, is a writer with Island Social Trends in the south Vancouver Island area.