Wednesday, January 9 ~ NATIONAL.

~ by West Shore Voice News

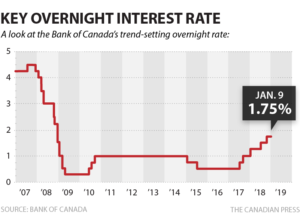

Oil, housing and trade are challenged in the Canadian economy. Based on that — and a lower than anticipated growth in inflation — the Bank of Canada today January 9 announced no change in the benchmark interest rate.

The bank’s idea of increasing the baseline interest rate is to try and maintain the rate of inflation at between one and three percent.

Raising or lowering the rates that borrowers get for lines of credit and variable-rate mortgages is impacted by all of this. For savers, no further rate increase keeps investment-earnings flat.

Canadians continue to be over-indebted. This scenario has been accruing for decades, and in particular since the economic crash of 2008 and the lengthy recovery period after that. Many Canadians do not earn enough income to sustain what might be considered a normal middle-class lifestyle or very simply to just raise a family, and so they borrow. Living paycheque to paycheque is not uncommon in this stressed economic scenario.

Under these conditions of slower-than-expected growth, businesses are less likely to invest but rather take a wait and see approach. This sort of response was seen more dramatically after the 2008 crash. Softer investment in turn affects jobs and overall economic activity.

Keeping things as they are with the interest rate today seemed to trigger a gain the value of the Canadian dollar at about 75.0 to 75.73 cents US.

The shift in the Bank of Canada approach from essentially micromanaging economic trends to instead ‘wait and see’ may well indicate that economic factors such as unemployment rates, homebuyer eligibility and sustained levels of household indebtedness are not being fully interpreted in a clear way forward.

Household debt was around 178% of disposable income in December 2018 (i.e. $1.78 owed for every dollar earned). The Bank of Canada said in May 2018 that the debt ratio of Canadians is at record highs, up from about 100% just 20 years ago.

Poloz himself penned in a May 2018 report Canada’s Economy and Household Debt and How Big is the Problem? that “debt is indispensable for our modern way of life”. The Bank of Canada Governor said in the report (remarks delivered at the Yellowknife Chamber of Commerce, May 1, 2018):

“For most Canadians debt is a fact of life, at least at some point. Borrowing can help someone get a higher education, or buy a new car, or purchase a home. Simply put, debt is a tool that allows people to smooth out their spending throughout their life.”

Poloz said last year that the amount of debt held by Canadian households has been rising for about 30 years, not just in absolute terms but also relative to the size of the economy. This could very well be because incomes are not keeping up with the cost of living.

At the end of 2017, Canadian households owed just over $2 trillion. Mortgages made up almost three-quarters of that debt.

The Bank of Canada today insisted that it remains committed to getting interest rates back up to neutral – i.e. the level where they are neither driving the economy forward nor slowing it down – but only “over time.”