Wednesday, January 23, 2019 ~ NATIONAL.

by Mary P Brooke, B.Sc. ~ West Shore Voice News

Despite all of today’s available science, it’s almost as if Canada’s Food Guide has gone retro while moving forward.

Saying the new food-intake guiding document [click here for PDF version] was reportedly developed based on evidence of what people are choosing and doing around food, it pulls back almost all detail about what nutrients are in which foods. Scientific specifics are quite minimal, and the Recommended Daily Allowances (RDAs) are gone.

The new guide was officially released on January 21, 2019.

This might rightfully and finally respect biological individuality and the wide variation in nutrient requirements based on age, gender and level of activity. But pulling back from any description about what nutrients are found in which foods is possibly with serious long-term consequences (the least of which is a poorly educated population, or worse, that key nutrients are being missed in a person’s diet on a regular basis).

With the emphasis now on food consumption behaviours, there seems to be almost an assumption that people know which foods offer which food values. That is a very large assumption based on education, income level, and food-buying intelligence.

If that information is no longer in the guide, where does that piece of education take place and to what level of consistency and reliability? At least with four food groups (scientifically proven to cover all the nutritional bases) there was a more reliable shot at hitting the right notes. Though it’s good that the imposition of serving sizes (as if one size fits all) is gone from the guide.

Truly there should be a concern about calcium intake over time. Without a designated dairy recommendation, it’s quite possible that calcium deficiencies (to various degrees) will emerge over time. That would include an increase in dental caries, bone growth impacts, and osteoporosis in persons who are aging.

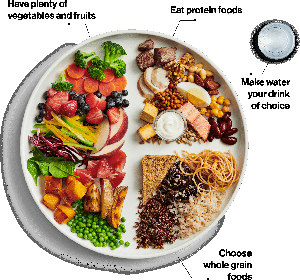

Looking at the new visual plate approach, perhaps it has been correctly observed that people eat what they like and the foods they are accustomed to either through circumstance or tradition. A ‘pick and choose’ approach is put forth in this new guide, which does respect seasonal availability of foods, income levels, and personal taste.

It’s good that “enjoy your food” and “be mindful of your eating habits” are included in the main four recommendations. “Cook more often” and “eat meals with others” — these recommendations come with an even more dramatic range of assumptions about time, finances, and social environment.

To simply say “make water your drink of choice” is to ignore the nutrient value in pure juices (yes, they contain ‘natural sugars’ but that is not the same as sucrose or added artificial sweeteners). And that eclipses those several glasses of milk daily which have been recommended for decades as part of reliable calcium intake. Also, a lot of water with a meal can dilute the digestive action of gastric acid and enzymes in the intestine that are required for the breakdown of food as it makes its way through the digestive system. A proper level of enzymes is essential for adequate breakdown and suitable absorption of nutrients.

In the new guide, dairy as a food group is gone. The main visual shows a plate filled half with fruits and vegetables, one-quarter with ‘protein foods’, and one-quarter with ‘whole grain foods’. Within each of those sections of the plate is a tremendously wide variety of nutrient options, but again the success of that approach depends on people knowing the best food options for their particular body type, health, and energy requirements.

Some foods are more difficult to digest, and some foods combined with others will impact the availability of nutrients from those foods (e.g. spinach contains oxalic acid which binds with calcium, making it less available to the body).

There is no detailing of oils vs fats. A lot of science in that area of human nutrition has been left out of this influential document.

Despite now half a century of people choosing to take vitamins, minerals and other supplements, there is no mention of nutrient supplementation (ideally toward optimum body performance) or enzymes (for optimum digestion).

While getting away from calorie counts, serving sizes and rigid daily quantities of food is a good direction for this official Government of Canada document to take, the overall vagueness of this new guide is in many ways leaving Canadians to sink or swim with regard to both daily and long-term health.

Despite that many Canadians will say they don’t refer to Canada’s Food Guide on any regular or rigid basis (which is probably why so much of it changed after 12 years), the document is a baseline that will influence health education in schools and community for years to come, if not generations (if you factor in from childhood and the rollover impact on the nutritional levels for future pregnancies).

This guide will be used in official capacities such as in schools, senior care homes, hospitals and penal institutions as well as by physicians and other health care providers. It leaves a lot of room for variety, but also a lot of room for error or omission that in many cases will have permanent impacts.

Mary P Brooke holds a B.Sc. in nutrition science with an emphasis on community health education and optimal prenatal nutrition.