Monday March 30, 2020 ~ WEST SHORE

by Mary Brooke, B.Sc. ~ West Shore Voice News

On a number of levels, most of our leaders and systems are coping well with the sudden realities of the COVID-19 pandemic. Adapting sometimes daily, and sometimes by the hour, is something quite new for governments and organizations that might otherwise take months or years to make changes to programs, processes or procedures.

In comes a microscopic coronavirus and everything changes. We can only hope that this disease which has come in like a lion will go out like a lamb. But it’s still too soon to know about that.

Governments, businesses, families and individuals — we are all being forced to adapt quickly, and in ways most of us have not prepared for.

Prompt changes are essential, but also the phrase “Calm keep and carry on” comes to mind. The myriad of changes upon us now as individuals, families, society and economies (both local and global) requires smart thinking and well-timed moves. Thinking outside the box is necessary in just about every situation, but without forgetting the need to keep people whole in themselves.

“This is it. This is our watershed, these coming weeks,” Dr Henry said in her joint presentation to media on March 30. “We will flatten that curve no matter how long it takes. This is our week to reinforce our effort. To do our part together while we’re staying apart.”

‘Flattening the curve’ has become a rallying cry for war against a microscopic enemy. Some are calling it an ‘invisible’ enemy, but in fact it is visible everywhere by way of the measures that we must take against it.

Prior to this sudden new reality, climate change activists were insisting that society rally around protection of the natural planet as if it were a war — drawing a comparison to how World War II elicited allied effort and a big shift in the economy toward producing needed supplies and equipment.

Well, we got our war. Mother Nature is being overrun by her own enemy (technically, science generally doesn’t ascribe the full definition of ‘life’ to a virus); things got out of balance through human hubris — we pushed the planet too hard. It’s not too soon to say that one of the silver linings of this pandemic is that for now we have fallen short of the predicted temperature rise of the planet that climate activists have been warning us about.

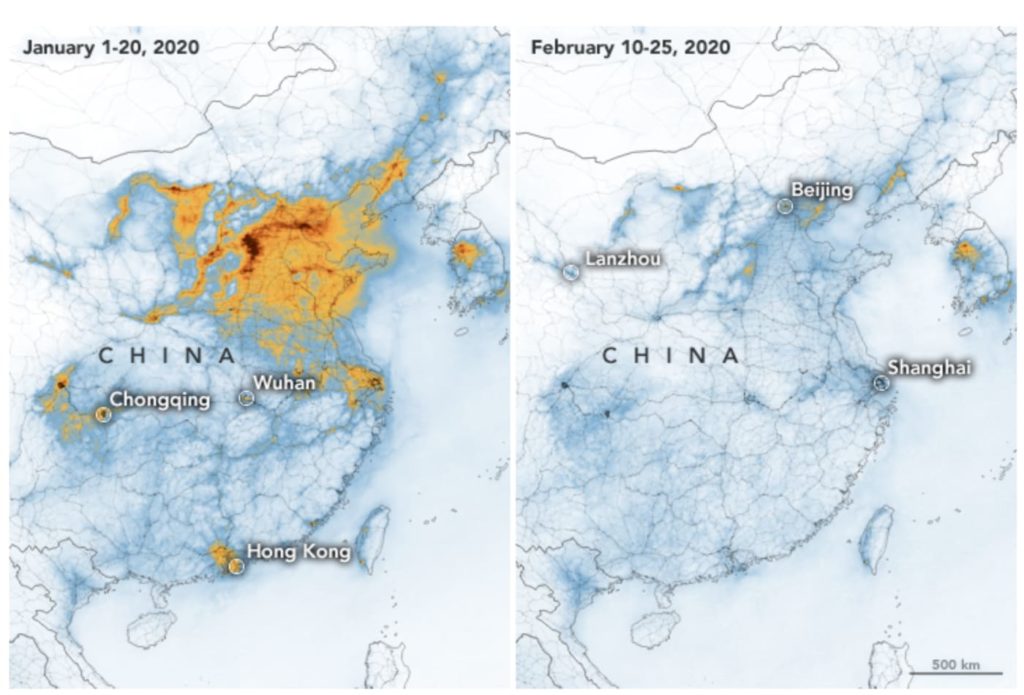

Case in point, thanks to satellite technology we can see there was significantly reduced pollution over Hubei Province in China when all manufacturing shut down there during their COVID-19 lockdown. And with the plummeted drop in airline travel, there is less fuel emission into the atmosphere as well. In that respect, hopefully the world does not return to ‘as it was before’. Pollution levels obviously must be contained and diminished.

On that point alone about polluting the precious envelope of air around this planet, we can see a ‘positive’ aspect of COVID-19, through its distinct messaging that it robs us of air. The final stage of COVID-19 infection is about the virus essentially eating away at lung cells — literally taking our breath away.

In BC, the public health direction is to manage the spread and presentation of COVID-19 infection strategically. That’s as opposed to a full lockdown. Though with the continued rollout of orders from the Provincial Health Officer Dr Bonnie Henry, British Columbians have been led relatively gently into technically now enforceable containment or even confinement (aka quarantine, when it’s a health scenario).

We’re faced with an infectious disease which has no cure or vaccine at this time, and every aspect of personal life, society and economy is starkly impacted.

We are asked to self-isolate at home, to maintain physical distance beyond what is instinctively normal for human beings, to limit our trips out for sustenance (like groceries), and to stop our trips out for anything other than essentials. Though it’s been a bumpy road to adherence on the part about ‘staying home’, for the most part that is now achieved in BC.

Here at March 30, look back to just earlier this month. People were still attending meetings, planning and attending crowd-style sporting events, going shopping whenever we pleased, and travelling any manner of distances as if nothing would ever change about that. Everything has changed about that.

Compare your life now to just two months ago. In a flurry your outward life (and your inner responses) have been set in reverse or in directions that feel odd. We look now like a slowed-down world of walking zombies, keeping our distance, focused on one task at a time, following orders that we’ve been invited to obey. And the world seems dirty; while we are paying much closer attention to personal hygiene, our streets and community spaces are neglected for now.

We trust our leaders, otherwise as a community we would not have collapsed so readily into this new reality that we are told is “for now, not forever”. Various observers of the necessary public health response to COVID-19 say it could take four to six months to pull out of having to live this way. And then the next fall/winter respiratory (aka flu) season will be upon us. So expect much of the same social containment in the winter of 2020/2021 while humanity awaits a vaccine by our amazing scientists.

The economic impact of COVID-19 has been massively destructive, rolling like thunder into our businesses, homes and lives. Shutting down an economy, step by step, has been the way to keep people separated. How dramatically we’ve seen in recent weeks how tied our prosperity is to our activity as social creatures. Keep us apart and we flounder.

At least with the information resource and social media that the Internet

and wireless technology make possible, most people are significantly buffered from the social isolation, other than the joy of human touch — the quintessential Canadian friendly hug is now out of the question. But our bank accounts and financial frameworks not so much. Individuals and families will be scrambling to pay rent in just one more day, many working around the hope of the promised federal supports (Canada Emergency Response Benefit or CERB) application for which opens on April 6, and associated provincial supports .

Many businesses are collapsing virtually overnight; even with a federal wage subsidy leapfrogging from 10% to 75% in a matter of days, many businesses still don’t have the reserve to hold onto employees. And businesses — even successful ones — don’t want to go into debt to ride this out… there’s no magic in that (even low rates of interest accumulate, and the load of unanticipated obligation is unwelcome).

How will individuals and businesses manage financially with regular obligations once economic recovery begins, while alongside is a new debt obligation? Prompt adaptation is key, while coping without various things in the short term.

On the medical side — while few highly explicit details have yet to be articulated about the course of the disease if one gets it, it is fairly safe to assume that the advanced stages where the virus attacks cells in the lower lungs are intense. A lack of oxygen is the ultimate outcome, leading to death if there is no intervention.

The only intervention which does work (presumably for most cases) is the use of a mechanical ventilator, of which BC has 705 at this time and BC Health Minister Adrian Dix says the province is working to get more. A shortage of ventilators would put lives at risk. In fact, Dr Henry says the earlier the intervention with a ventilator, the better the outcomes. That stance can underscore hope among British Columbians that we may — in addition to flattening the curve — be ahead of the curve, with a strategy to get ahead of the disease, not catch up to it.

As a side note on ventilators — usually deciding to put a patient onto a ventilator is based on signs of respiratory failure (increased breathing rate, increased CO2 in the blood, and emotional signs of distress including confusion). Being attached to a ventilator means that medical staff can adjust the rate that it pushes the air and oxygen into the lungs, and adjust the oxygen mix.

Getting hooked up to a ventilator sounds like something you’d want to jump on right away if you’ve got a confirmed case of COVID-19 and it becomes more severe (many cases are mild and can be dealt with on your own at home).

But intubation is not like taking a quick pill. It requires insertion of a tube down your throat and into the windpipe. It is probably best done under some level of sedation or muscle relaxant. There is almost always some spewing of body fluids, and for this the health care team wants to be fully protected by N95 mask or visor, full gown, and gloves (collectively referred to as personal protective equipment or PPE). And it takes skilled medical personnel to perform that intervention.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is in high demand now by the health care system in general; shortages in some jurisdictions are being reported. Shortages of PPE seem to be the weakest link in the strength of a hospital system to win against what could be an onslaught of COVID-19 cases soon.

It’s evident in these early days of COVID-19 response that responding quickly and with the best available public health response is key to riding this crisis. To beat COVID-19 means to ride its bronco back for a while, until we find those treatments and a vaccine. It’s a rough ride. Those who had some sense of preparation are having an easier time of this initial phase. But everyone is going to lose a round or two — socially or economically, as well as sadly health-wise for some. The death tally from COVID-19 in BC so far stands at 19.

With self-isolation comes the challenges of dealing with the range of mental and emotion responses. Once we have a vaccine and a restored economy — we’re looking 24 to 36 months for all that — we’ll be left with the trauma of it all. The impact of COVID-19 will reverberate for years, if not decades, just as did the impact of World War II did on the psyche of our families and society.

In this early part of the 21st century we almost had it beat … life on this planet had many challenges, but overall it had forward momentum and a reasonably good lifestyle for many. This setback is an excellent opportunity to remember with humility our fragility in a big powerful universe.

===== Mary P Brooke has a B.Sc. in nutrition (with studies in microbiology, biochemistry, and community education), as well as a second major in sociology. Her editorials are most often through the lens of socioeconomics as a way of exploring the social ecology of our world.